The original article in Spanish can be read here.

ADRIÁN FALCO

Latin America and the Caribbean have two particularities that reveal, almost like an axiom, a reality that is in every part of our continent. The tremendous wealth that the region generates is concentrated in very few hands and poverty, which does not stop growing, affects millions and millions of people. To be more exact, 30% of Latin Americans are poor. This criminal inequality is measured in horrifying statistics. One of them is that 1% of the population in the region owns 43% of the wealth. In simpler terms, if we want to distribute 10 dollars among 10 people, only one of them will take 4 dollars, while the remaining 6 dollars would have to be divided among the other nine people. This is the injustice of capitalism and neoliberalism.

It is clear, demonstrated from growing research, that the solution to resolving these inequities is in the tax systems. These systems, as you can imagine, are not abstract but have become a terrain of political dispute whose norms and scope, which are tailored to the elites, are the most effective tools to change history. These systems that collect taxes do it poorly and, as a result, get little. This is a result of two important, but not decisive, characteristics: low tax burden and regressive taxes systems. When we talk about tax burden, we are talking about the weight that taxes have on the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) the average is 27.1%, while in the most advanced countries (OECD) it reaches 34.1%. What does this mean? That in Northern countries, more taxes are paid.

Then we look at the second aspect: the tax revenue system is based on regressive taxes. This system, present in all Latin American countries, relies upon indirect taxes. Indirect taxes are taxes paid by the entire population and do not take into account the contributory capacity of the person who pays them. To simplify: the Value Added Tax (VAT) or consumption tax is paid by everyone regardless of wealth. That is, rich and poor pay the same level of tax. The VAT is an example of this. If the State collected more through direct taxes – that is, taxes on high net worth, windfall profits, etc. – workers would be happier because those who would pay the most would be those who earn the most. Attention before continuing! This is tax justice.

Let’s not stop with this explanation alone, let’s go to the statistics of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) to have an evidence-based notion. In European countries, taxes on the income of high-net-worth individuals and company profits represent 60% of tax revenue on average, measured based on GDP. In Latin America, on the contrary, it is equivalent to 43%. On the other hand, while the VAT, or general consumption taxes, make up 50% of the revenue in our region, in the OECD it only makes up 32.1%. In Europe, those who pay the most are those with the most purchasing power, while in our region it is exactly the opposite.

Now, to the two particularities that we mentioned we have to add some elements that directly harm tax revenue and, the possibility of obtaining resources to finance public policies. Without resources there is no state. Or, at least, not the state we want. The elements that impact low tax revenue are: high tax expenditure in the form of investment incentives; resistance of elites to accept tax reforms; structural problems such as high labor informality, evasion and avoidance; tax planning exercised or understood as evasive maneuvers of people and companies (use of tax and financial havens, offshore companies, etc.).

But let’s go in parts. When we talk about “tax expenditures” or “tax exemptions” we are referring to those measures that governments take to, for example, attract investments. It may happen that they eliminate taxes and/or benefit certain sectors with tax reductions with the promise of the investor to “generate jobs” and “improve infrastructure in a city.” We like to call it privileges in exchange for nothing. Simply because the evidence indicates that companies that invest in our countries are not determined by the taxes they will have to pay. These companies have already done their tax planning using their entire offshore company structure to triangulate different operations and thus determine, in advance, how much taxes they will pay and where they will do so.

For this, it is always good to remember a response from Paul O’Neill, who in 2001, when appearing before the U.S. Senate defending his candidacy to be Secretary of the Treasury, said in relation to what specific changes he would apply to taxes to increase investment in companies. companies. O’Neill responded bluntly: “As a businessman, I never made an investment decision based on the taxes I had to pay. If you’re giving away money, fine, I’ll take it. If you’re trying to give me tax incentives for something I’ll do anyway, I’ll take it. But good businessmen don’t do things for tax incentives.”

So, and based on this background, we can say that Latin America and the Caribbean loses 3.7% of its GDP annually due to tax exemptions or privileges for companies and the richest in exchange for nothing. What could be done with those resources? In principle, double investment in education in all Latin American countries.

Reviewing what we have so far: regressive tax systems based on indirect taxes, a wide gap in fiscal pressure compared to the OECD (12 percentage points difference to the detriment of our region), and a high and disproportionate tax expenditure. But the question that must be asked now is: in what situation is this reality occurring?

According to the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), the loss of revenue on the continent due to evasion of income tax and value added tax is around 433 billion dollars, which is equivalent to 6.7% of GDP. On the other hand, and according to the Tax Justice Network, multinational companies are transferring profits worth $1.15 trillion to tax havens each year, representing losses of $311 billion annually in direct tax revenue for governments around the world. world. ECLAC estimated that in 2015 illicit financial flows derived from manipulations of trade prices would have been around 93 billion dollars or 1.5% of regional GDP.

In the case of individuals, the use of low or no tax jurisdictions to hide assets is also a widespread practice. These tax havens, in addition to a low tax rate, offer schemes with little control or regulation, particularly regarding the origin of the funds and information of beneficiaries. According to a study by Vellutini, titled “Estimating international tax evasion by individuals”, the wealth held abroad would have reached 7.8 trillion dollars worldwide in 2016, equivalent to 10.4% of global GDP.Today in Latin America and the Caribbean, the wealth of 107 billionaires in the region amounts to 408 billion dollars.

If we return to our allies, statistics, we can identify that OECD countries collect four times more in personal income taxes, relative terms to the size of their economies. While in Latin America the revenue from this tax represents 2.3% of GDP, in OECD countries it represents 8.1%. The same occurs with the property tax, which in our region is at levels of 0.8% of GDP, while the average for OECD countries is 1.9%. There is fiscal space to tax the richest and not resort to adjustment or the chainsaw.

Another example is offshore wealth. It is estimated that 22% of Latin American wealth is not in our region, but in tax havens. We must fight incessantly to collapse the network of offshore financial services, which allows money to be hidden outside our borders and away from the reach of the treasury; the constitution of shell companies; the triangulation of operations with intermediaries; the triangulation of operations with intermediaries abroad and other practices.

To begin to win this battle against tax fraud and collect more to better redistribute and repair the social fabric, it is urgent to take measures from governments, both individually and collectively, taking into account some of these suggestions that we are promoting from social organizations and academia.

- Access to financial information and exchange of information agreements: it is very important that tax administrations, financial market control bodies and also civil society have full knowledge of the activities carried out both inside and outside our countries in relation to to finances. This measure will only be successful with more agreements between countries that enable the exchange of information.

- Public registry of beneficial ownership and assets: Having public records of owners of companies, trusts, foundations and assets (vehicles, real estate) will help us know who owns what and where.

- Toughen penalties for tax crimes: it is important to modify the criminal codes so that those who financially defraud the State and/or evade taxes are criminally punished with effective prison sentences.

- Regional and global tax coordination: advocate for the strengthening of supranational spaces for the exchange of experiences and public policy recommendations. The Tax Platform of Latin America and the Caribbean (PTLAC), promoted by ECLAC and some governments in our region (Colombia, Chile, Brazil, among others), is an example. At the same time, strengthen the recent Tax Convention at the United Nations, which seeks to democratize the debate on global taxation.

- Strengthening tax administrations: provide the tax administrations of our countries with both human and technological resources. The fight against tax evasion and avoidance is constantly becoming more complex thanks to new forms of fraud and to combat these practices, continuous training of its officials is required.

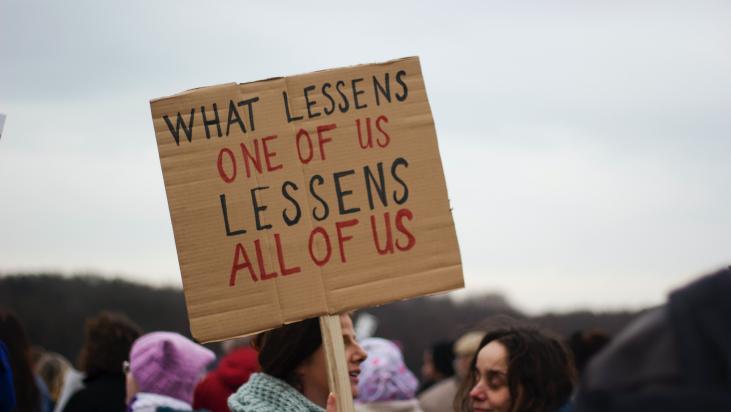

Finally, and entering a more colloquial level, we have to ask ourselves once again why it is important to debate the tax system and taxes. We do it because inequalities are not a number in an Excel, but inequalities have, although it may sound corny, a face, voice, name and surname, And when we draw a line between people, truncated public policies and tax fraud, the severity of the issue intensitifies.

In the La Colmena neighborhood of Quito, Ecuador, lives Juan Córdoba Sánchez. He is a bricklayer. Day after day he goes to a square in his neighborhood frequented by construction contractors who demand his labor force. Juan lives with his 93-year-old mother and his 16-year-old niece. He pays a rent of $60 a month for his one-bedroom house. He earns from his work 100 dollars a month when he is lucky. At the same time that Juan fights daily for those 100 dollars, Ecuador loses 7.7% of its GDP to tax evasion, close to 7 billion dollars a year. How much rent could Juan pay with that money? How many rooms could he build? What care could he give to his mother? The tax justice we are pursuing is called Juan, his mother and his niece.

In the Bañado Sur neighborhood on the banks of the Paraguay River, in the city of Asunción, lives Mariel Rodríguez, who is the mother of five girls and the sole economic, physical, and spiritual supporter of her home. Her income from collecting cardboard on the street does not cover her and her daughters’ food. She receives two bonuses from the State: the family food allowance, which is equivalent to 90,000 guaraníes, and the family allowance, 40,000 guaraníes. She adds, in total, 130,000 guaraníes per month, the equivalent of about 18 dollars. They say in the neighborhood that “when the river rises, poverty floats.” At the same time, Paraguay is the country with the lowest tax pressure in the region: 13.4% of GDP. There the rich don’t pay taxes. In 2021 it came to light that the Mobile Zone company had evaded taxes of $600 million over five years. A good house in Paraguay, in the Luque neighborhood, for Mariel and her daughters could cost, on average, 800 million guaraníes, about 100,000 dollars. Six thousand women like Mariel would have had access to housing if the State had persecuted, imprisoned and collected those taxes from evaders. The fiscal justice here is called Mariel and hers are five children.

But we can also talk about quality public services that do not include everyone. In Guatemala, for example, the lowest investment in education in the region is recorded by comparison. Investment in primary and pre-primary (kindergarten) is meager and it is also very difficult to guarantee bilingual education. At the same time, the country has a tax pressure of 12% of GDP and an income tax evasion of more than 2,000 million dollars per year. How many pre-primary classrooms could be built? How many teachers’ salaries could be paid? Fiscal justice, today strongly promoted by various reforms, is called here quality education for all.

It doesn’t matter where you live. There will always be a Juan, a Mariel, a school without heating or without blackboards. We cannot normalise this reality. There is a possible path by reforming the tax system. Fiscal justice is always, and everywhere, social justice.