Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters

During the fifteenth session of the Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters held on 17-20 October in Geneva, the committee elected two co-chairs: Eric Mensah from Ghana and Carmel Peters from New Zealand.

The tax committee was established in 1968 pursuant to the ECOSOC resolution 1273 (XLIII) of 4 August 1967 as the Ad Hoc Group of Experts on Tax Treaties between Developed and Developing Countries. On 28 April 1980, the ECOSOC gave a broad title to the Group, namely, “Ad Hoc Group of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters” and increased its membership from 20 to 25 drawn from tax administrators of 10 developed and 15 developing countries and economies in transition. And on 11 November 2004 the ECOSOC renamed the Group the Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters.

The Committee of Experts finds its mandate in ECOSOC resolution 1273 (XLIII) and is responsible for keeping under review and update, as necessary, the United Nations Model Double Taxation Convention between Developed and Developing Countries and the Manual for the Negotiation of Bilateral Tax Treaties between Developed and Developing Countries. It also provides a framework for dialogue with a view to enhancing and promoting international tax cooperation among national tax authorities and assesses how new and emerging issues could affect this cooperation. The Committee is also responsible for making recommendations on capacity building and the provision of technical assistance to developing countries and countries with economies in transition. In all its activities, the Committee gives special attention to developing countries and countries with economies in transition.

The composition of the committee is therefore an important aspect in ensuring inclusivity and a balance in representation. The 25 members of the committee are nominated by Governments and they act in their expert capacity. They are then appointed by the UN Secretary General. They are drawn from the fields of tax policy and tax administration and are selected to reflect an adequate equitable geographical distribution, representing different tax systems. For the first time, the composition has changed, with members from the OECD now significantly outnumbered. And this is significant at the moment to ensure that all countries have a seat on the table to make international tax rules.

The last 25-member committee had 12 members from OECD states and 13 from outside the OECD. (4 were G20 members). Therefore, 16 of the committee came from countries that currently sit at the table of international tax rulemaking, while only 9 were outside that particular tent. This contradicts the UN tax committee’s developing country remit.

In the current committee, 8 members are from OECD countries, a further 7 members come from countries that are Committee on Fiscal Affairs (CFA) participants or Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) process associates. 10 of the 25-committee members come from countries that do not have a seat in the OECD and G20’s main tax discussions.

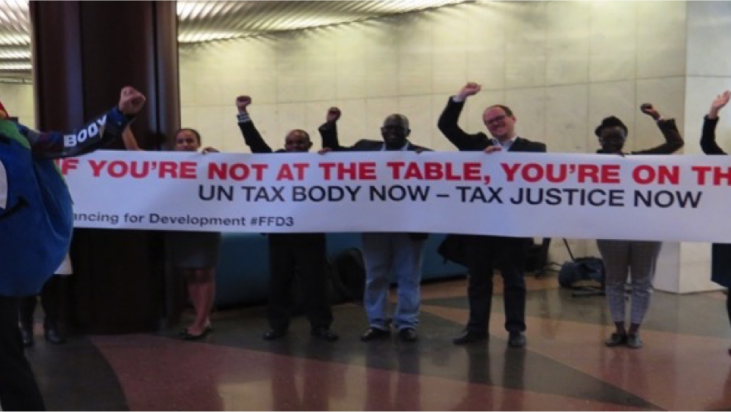

The GATJ therefore advocates for the establishment of an intergovernmental UN tax body that has representation from all countries on the table on an equal footing. This UN body is envisioned to be a forum that to includes all countries on the table to discuss tax matters and the international financial architecture rule making. According to Dereje Alemayehu, the GATJ Chair “If you are not on the table, then you are on the menu.”

This is because, at the UN tax committee, not all members have equal influence. Much of this variation is due to the personal expert capacity in which members attend. As a result, outcomes are a product of, among other things, their experience in international negotiations, how much of a mandate they have from the country that nominated them to adopt contentious positions, the strength of their informal relationships, their fluency in English, and how effectively they caucus in blocs. There is often a trade-off, for example, between seniority and technical knowledge.